- Home

- Michael Challinger

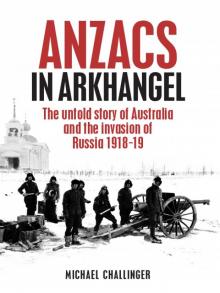

ANZACs in Arkhangel Page 13

ANZACs in Arkhangel Read online

Page 13

In spite of these reservations, most Australian coverage about Russia was inflammatory. Scaremongering about the horrors of the Bolshevik regime alternated with predictions of its imminent collapse. The ‘Red Terror’ was written up to the point of hysteria and even sceptical readers were apt to be worn down by sheer repetition. For example, in a single week the Advertiser in Adelaide ran these headlines:

SHIFTY BOLSHEVIKS

In German Pay

BOLSHEVIK BRUTES

Heartless murderers—No conscience left

RUSSIAN CHAOS

Bloodthirsty Bolsheviks5

Partly thanks to the press, Bolsheviks became conflated in the public mind with Russians in general. With the war over, Bolsheviks—and by extension all Russians—replaced the Germans as an object of hatred.

Anti-Russian feeling was strongest in Queensland where about four thousand made up Australia’s largest Russian community. Serious violence against them broke out on 23 March 1919.6 It started when several hundred Russians and leftists gathered at the Brisbane Domain. (One was the legendary Monty Miller, the octogenarian veteran of the Eureka Stockade, who wore a red rosette, a red tie, a red scarf wound around his hat and had his historic Miner’s Right pinned to his lapel!) The group defied a small police cordon and unfurled their red flags and banners.

Remarkably, it was a criminal offence to fly a red flag. Regulations introduced in 1918 under the War Precautions Act prohibited the display of flags or emblems of any group ‘disaffected with the British Empire’.7 The measure had been aimed at Irish Republicans but also had the effect of criminalising the carrying of the red flag, the symbol of the Bolsheviks.

Brisbane’s Daily Mail first incited anti-Russian feeling—and then reported it. The Bolshevik here looks more like a Turk than a Russian, but the message is plain. (Daily Mail, 26 March 1919)

Enraged by the red flags, ex-servicemen and Empire loyalists formed an opposing force and broke up the leftist gathering in a wild brawl. They then converged, two thousand strong, on the hall of the Russian Association in South Brisbane, intending to burn it down. The police did little to protect the hall and the mob was seen off only by revolver shots from the beleaguered Russians.

Brisbane’s Daily Mail was no model of sober analysis. (Example: ‘Bolshevik swine are mere bloodthirsty cut-throats’.) The next day8 it ran a lurid account, headed ‘Queen Street Russianized’, which described gloating Russians smiting the outnumbered police with sticks and flagpoles.

The Mail predicted more violence—and facilitated it by giving details of when and where the anti-Bolshevists would assemble. That evening a huge mob of about seven thousand descended on the offices of the Russian Association. They carried a large Australian flag and their stated aim was ‘to clear out of Queensland all the dirty Russian mongrels’.9

This time the disorder was too great for the police to ignore and they confronted the crowd in military formation with rifles and bayonets. The night echoed to revolver shots, the thud of rifle butts, the clatter of hooves, and the crash of breaking glass. The Russians’ hall was wrecked, as were nearby shops and boarding houses owned by ‘foreigners’. The mob bashed any Russians or Jews they caught, as well as anyone else unlucky enough to be singled out as a Bolshevist sympathiser.

Nineteen police were injured and three police horses (including one named ‘Czar’) sustained bullet wounds. The press played down the number of civilian casualties, but they ran into the hundreds. The police commissioner himself was among the wounded, as was the magistrate who later sentenced the flag-wavers to gaol. Both were accidentally bayoneted by the police in the melee.

The role played by the Mail was an extreme example of anti-Russian feeling. The popular press took every opportunity to demonise the Bolsheviks and pandered shamelessly to their readers’ racial prejudices. Newspapers usually referred to Bolshevik bodyguards as ‘Chinese’ and Bolshevik executioners as ‘bloodthirsty Mongolians’.10 It was often implied that somehow the Jews were behind all the trouble in Russia. And as if that wasn’t enough, the hated Germans were also involved: ‘Bolshevism is an insidious political disease deliberately fostered by Germany … to regain by foul means the position in the world she has lost in fair fight’.11

As for sex, nothing horrified the conventional classes more than the Bolsheviks’ alleged ‘repulsive bestiality, lawlessness and lust’ and their contempt for the institution of marriage.12 One bizarre scare story was that of the ‘Saratov Manifesto’, a purported decree for the nationalisation of women. Most Australian papers happily took up the story from Britain, where the original headline in The Times had read:

HORRORS OF BOLSHEVISM. A CRY TO HUMANITY.

MONSTROUS TREATMENT OF WOMEN13

According to the so-called decree, since the best women had always been ‘owned’ by the bourgeoisie, all females between seventeen and thirty-five were henceforth declared the property of the whole nation. Male citizens were given the right to ‘use one woman three times a week for three hours’. As a concession, married men who now had to share their wives, could go to the head of the queue without waiting their turn!

The decree was issued in the name of the anarchists of Saratov (or sometimes of Samara, Yekaterinburg or Kronstadt, entirely different cities thousands of kilometres from each other). Press reports failed to distinguish between the Bolsheviks, who condemned the ‘decree’, and the anarchists, who were a thorn in the side of the Bolsheviks and were later liquidated by them.

Though the decree was completely spurious, only one paper saw through it: Melbourne’s Truth.14 Unfortunately, Truth was a racy, antiestablishment weekly which respectable people didn’t read. So the fake decree continued to serve its purpose of inflaming public opinion against the Bolsheviks.

As for the military situation in Russia, coverage at best was incomplete and heavily slanted. At worst, it was simply false. Bolshevik advances were reported in short items of a paragraph or two, while statements from the War Office in London were written up prominently and at length.

The Australian press, for example, seems not to have reported the mutiny of Dyer’s Battalion at all. And while the loss of Onega made the papers, the first report was published three weeks after the event and failed to mention that White troops had changed sides. Coverage by the Melbourne Argus was typical:15 two small paragraphs buried, containing quotes from the British War Office which put an obvious spin on the story.

The left-wing press was no match for the mainstream papers. While there were labour dailies in several state capitals, they struggled to counter the flood of anti-Bolshevik propaganda. Some, too, discredited themselves by resorting to the same sort of exaggeration and abuse of which they accused the conservative press. Union weeklies poured scorn on the so-called ‘Red Terror’, but their circulations were small and they were preaching to the converted.

For the Left, the lack of accurate information about Russia was a major problem. The Left was poorly informed about Allied moves in Russia and clearly didn’t know of the Australians who were fighting there. Getting independent information was impossible. When the Victorian Socialist Party resolved to send its own observer to Russia, the government refused him a passport.16

wing artist Claude Marquet drew cartoons for a weekly publication by the Australian Workers’ Union. He made the same point in almost every issue—that the right-wing press was duping its gullible readers. In other cartoons Marquet showed capitalists stirring up fear and hatred by portraying Bolshevism as a dangerous bear, a bogeyman and a ferocious scarecrow. (Australian Worker, 6 March 1919)

Only two papers seem to have twigged to the presence of Australians in Russia. One, the Brisbane Worker, wrote: ‘It is not a bad tribute to the 400,000 Australians who enlisted that only 19 [sic] of their number can be found willing to enlist to fight against the Russian workers and help to bring back the brutal despotism of the Czar’.17

The other was Truth again. On 24 May it ran a piece headed ‘Australian blood—shou

ld it be shed to set up a tsar?’, which blamed the Intervention on Russian reactionaries and international moneylenders. It argued that if Australian troops were ‘seduced into this foreign adventure’, they should not be wearing the Australian uniform, one which ‘has not yet been stained by anything of which an Australian need be ashamed’.

Truth called for Parliament to condemn the sending of troops and to declare:

that we do not approve of the so-called ‘relief’ battalion: that we will not assist in the equipment or maintenance of that unit: and that we will not consent to any member of it wearing even a colourable imitation of ‘the Australian uniform’.

Parliament did no such thing. All that happened was that Frank Brennan, the radical Melbourne MP, asked a question in federal Parliament. On 8 August 1919, referring to the Diggers rumoured to be in North Russia, he asked:

Having regard to the fact that these soldiers were not recruited and are not controlled by the Australian government, will the honourable gentleman take the steps necessary to see that the good name of the Australian soldier, and of Australia itself, is not tarnished by association with what so many good Australians conceive to be an iniquitous invasion upon the Russian proletariat?18

Prime Minister Billy Hughes was still on his way home from the Peace Conference at Versailles, so it was William Watt, the acting prime minister, who replied. He said he didn’t know anything about Australians in Russia, but promised to make enquiries. On 21 August a follow-up question was similarly fobbed off and nothing further was ever heard in Parliament on the subject.

11

ON THE DVINA

JULY 1919

BACK in North Russia, the picture was the same, with the Australians divided between the two fronts. The main detachment was based on the Railway Front while the smaller group, of about two dozen, remained on the Dvina. After the mutiny of Dyer’s Battalion, these men were moved into the forward zone where they carried out a succession of raids and aggressive patrols.

Inland from the river, theirs was a territory of no roads, countless tracks and few maps. Such maps as existed omitted important natural features: sizeable rivers were often unmarked and the huge Selmenga forest, for example, wasn’t shown at all. Accurate, large-scale maps were badly needed and many of Keith Attiwill’s patrols were made to gather information for the map-makers.

Patrolling behind enemy lines was dangerous. The risks were twofold: ambush by the enemy and treachery by their guides. Local peasants had been given British uniforms and pressed into service as guides. Having spent their lives in the forest, they knew it well and, according to some British officers, were ‘wonderful’. Keith Attiwill disagreed entirely and thought them utterly untrustworthy. Some, it was said, had been taken prisoner five or six times and fought on each side alternately.1 Attiwill himself knew of cases where Russians started the day on the White side, went over to the Reds at noon, and finished the day fighting with the Whites again!2

Attiwill’s earlier carefree attitude changed. He dreaded the monotony of long marches through endless, silent forest: ‘I am not ashamed to remember how that damned interminable Russian forest … used to frighten me’.3 Although in books, he said, it sounded fun to be a scout, the reality was very different. In enemy areas the men risked their lives in nerve-racking games of hide-and-seek. Sometimes half a dozen of them were hunted through the forest in a life-and-death chase. It was an ordeal which changed those who underwent it. Having experienced how it felt to be hunted, the British lieutenant commanding the Aussies’ platoon forbade hunting on the family estate after his return to England.4

Aussies and others take a smoko somewhere in North Russia. Australian troops retained their AIF slouch hats, though one man here appears to sport a Russian fur hat. (AWM A04700)

Royal Fusiliers bathe and wash their clothes in the Dvina at Bereznik, across the river from their base at Osinova. Since the sun sets only briefly during the northern summer, this picture could have been taken at almost any time of day. (IWM Q 16155)

On one occasion Attiwill was among a group which penetrated into the forest behind the Bolshevik strong point of Seltso. He and the intelligence officer left the main group of thirteen and approached as close as they dared. Within a few metres of one outpost they were challenged and forced to shoot a sentry. This alerted the enemy, who immediately gave chase.

Doubling back to rejoin the group, the two men lost their way and were chased for 5 versts through swamps and thickets. By a miracle they found the others, who then joined them in a mad dash for safety. Attiwill says they were strung out as if at the finish of a mile race till they got across a stream and found relative safety. It took them hours more to regain their lines.5

Ernest Heathcote, the man who had joined the AIF at sixteen under a false name, recounts another patrol.6 He says the first call for volunteers was a failure. The men had so little confidence in the officer in charge that only five put their hands up. Once a sergeant whom the men respected was detailed, another twenty takers were soon found.

The group set out at 10 pm in broad daylight, each man armed with a rifle and 120 rounds of ammunition, a bayonet, a machete, four Mills bombs, and two days’ rations. The machetes had been issued in England and, thinking at the time that Russia was always under snow, the men had laughed. In fact, the bush knives sometimes proved handy in the dense undergrowth.

The patrol was ordered to penetrate as far as possible and investigate the low level of the river. After a trek of 20 kilometres (and a false alarm with some stray cattle) they heard the unmistakeable report of a Bolo rifle and ducked for cover.

Soon the rifle fire increased & I heard the dull thud of a Mills bomb &we fixed bayonets & rushed forward. We found our advance guard mixed up in a hand to hand tussle with twenty-two Bolshevik Mongolians. The bayonet soon got to work & British grit & good weilding [sic] of the bayonet soon told & we were not long in overpowering the Bolos. No man escaped and as dead men tell no tales all were killed outright.7

Heathcote adds that three of their own men were killed and others were wounded.

While men in the field were so engaged, those billeted further back on the river had an easier time. In fact, before embarking for Russia, British officers had been promised the chance of ‘good sport’ and advised to bring fishing rods and shotguns. A Major Gawthorpe of Grogan’s brigade spent a lot of time on the Dvina fishing, shooting, eating and drinking. His diary includes these entries:

29 July—Singsong with host’s daughter.

30 July—Entertained Russian general, wives, staff.

31 July—Arranged to get ex-Dyer prisoner sent back to be shot. Had a singsong in Mess.

7 August—Drove off to the sports in a four-in-hand with Rotes and Foster as postilions.

16 August—Went fishing and duck shooting.

20 August—Fishing, started draughts tournament.8

While officers like Gawthorpe lived and ate well, it was different at the front. Despite the resources of the Relief Force, rations at the forward posts were substandard. They consisted of bully beef (from Argentina), weevilly rice, army biscuits and ‘tons of tinned mush called marmalade’.9 In theory there were also dehydrated vegetables, tea and canned butter. It was a diet which led to bouts of dysentery and stomach troubles.

Life on the river for the naval crew was full of contrasts. One British naval officer was Basil Brewster, who later migrated to Australia and rose to high rank in the Royal Australian Navy during World War II. In Russia he served aboard several gunboats, as well as spending time ashore as one of a naval landing party.

Brewster records how bombardments by Red gunboats often resulted in stunned fish floating to the surface.10 Those from shell bursts falling short of the target used to float downstream towards them and the deckhands would scoop them up in nets. Many engagements were fought while the ships were at anchor so the stokers, who otherwise had no work to do, were sent out in small boats on fish-harvesting duties!

As a membe

r of a shore party, Brewster helped man 12-pounder naval guns. He once spent three weeks living in a bivouac of branches and canvas, the whole time in wet clothes. In compensation, he spent the next two weeks comfortably billeted in a village, passing his time duck shooting.

In mid-July the bush telegraph hinted at a big ‘stunt’, to be followed by evacuation. Headquarters at Arkhangel tried to scotch the rumours, warning that anyone who repeated them was helping ‘the dissemination of obviously Bolshevik propaganda’.11 Needless to say, the rumours were true. General Sir Henry Rawlinson was being sent from England to coordinate the withdrawal and take overall command of both Arkhangel and Murmansk.

Rawlinson was a famous general who had commanded the British 4th Army on the Western Front and was an expert in tricky situations. London was worried the withdrawal might turn into a shambles and wanted it placed in a safe pair of hands. Rawlinson’s perception was that the government was ‘in a hole’ and that he was doing them a favour by helping them out. He recorded in his diary: ‘Winston thanked me profusely for going, saying it was a very sporting thing to do’.12 Rawlinson had been promised a barony for his trouble.13

The general was able to set his own terms. Churchill allowed him a large staff (21 officers, 14 clerks, 17 batmen and 30 other ranks) and promised him extra infantry, machine-gunners, field batteries and a detachment of tanks. The six tanks arrived complete with their mascot, messenger dog ‘Nell’, who had recently recovered after being wounded in France.

Rawlinson’s appointment caused temporary alarm in Britain. Some of the press thought it signalled an escalation of the campaign, rather than its end. The appointment also ruffled Ironside’s feathers, though the government mollified him, and Maynard, the commander in Murmansk, with promises of a knighthood each.

Unlike the Australians, the Canadians formed a separate official contingent. Here, comfortably seated, a Canadian gunner supervises the unloading of a barge on the Dvina in May 1919. Coils of barbed wire lie at his feet. (Outram collection, Library and Archives Canada PA-037404)

ANZACs in Arkhangel

ANZACs in Arkhangel