- Home

- Michael Challinger

ANZACs in Arkhangel Page 15

ANZACs in Arkhangel Read online

Page 15

Heathcote was among the wounded. As a machine-gunner, he had been engaging the Bolo gunboats after Sluda was taken. Once the Bolo marines landed (he puts the number at two hundred, ‘a lovely target’), he concentrated on them until the shell from the Bolo naval gun caught his team.11 One of his legs was broken, and an ankle and elbow smashed. That was his condition when they started their nightmarish trek to safety.

As the column headed into the forest they picked up stragglers from other units. It was now a ragged, awkward formation, totally dependent on the local guides. Many of the prisoners were cowed and frightened, but some were recalcitrant and others again were simply waiting the first opportunity to turn on their captors.

After four or five hours the column came to the River Sheika, which that year was more a swamp than a river. The crossing itself was about 100 metres wide, bridged by a series of logs and planks, part of it with a rough bush handrail. A rearguard held the southern end while the party started to cross in single file. Some prisoners were carrying the wounded and the whole unwieldy line was hampered by its equipment and the civilians. Getting across was taking time. About half were over and the rest were strung out along the planks.

With the Bolos catching up, a message was passed along the line telling the men to get a move on. Fifteen minutes later the rearguard engaged the Bolos but were too few to hold them off. As soon as the enemy got within range, they opened fire.

The men on the planks were at their most vulnerable. Chaos reigned. Some made a mad rush for the other side; others dived flat. Prisoners carrying the stretchers dropped them or tipped the wounded into the swamp. Many prisoners leapt in themselves to escape the hail of bullets, only to find themselves sucked into the mire. Two machine guns were hurriedly set up on the far bank to hold off the enemy while the stragglers scrambled across.

Among those crossing was a twenty-year-old British lieutenant. Strictly, his name was Charles Henry Gordon-Lennox, but as the eldest son of the Earl of March, he held the title Lord Settrington. He had mixed in the highest circles since childhood: he’d been a guest at the Prince of Wales’ ninth birthday party and a pageboy at the King’s coronation in 1911. From Eton he had gone straight to Sandhurst Military College and the Western Front.

For the last seven months of the war Settrington had been a prisoner of the Germans. Soldiering was the family tradition and to see more action he had volunteered for Russia. Bad luck found him crossing the swamp when the Bolos opened fire. Chance saw a bullet strike him in the chest.

One of the rearguard, Arthur Sullivan, was nearby as Settrington crumpled and fell into the swamp. Sullivan plunged in after him. Up to his armpits in black ooze, he took hold of the wounded lieutenant and passed him up to others still on the planks.

Then, as Bolo bullets continued to rake the ground, Sullivan helped two more fusiliers in the same way. A fourth, further away, was in extreme difficulty but Sullivan was out of his depth now and unable to reach him. He waded back and grabbed a length of broken handrail, then struggled again towards the drowning man—who succeeded in grasping hold of it. Others then hauled both men back onto the planks and helped them reach the far side.

Heathcote wrote of the scene: ‘Many fell only slightly wounded but once in that soaking, sucking morass there was no hope of escape … I saw some sad sights along the remainder of that swamp—legs and arms sticking out of the mud and others on their last gasp. In that action alone we lost 42 when the count was taken.’12

The column lost both its guides in the shambles: one was dead, the other had fled. As the Bolos pressed their pursuit, the British column disintegrated into smaller groups. It was two o’clock in the morning.

In Heathcote’s party there were thirty-nine men still fit to fight, another three on stretchers and over eighty prisoners.13 One of the captives took over as guide but led them into a Bolshevik camp. The enemy turned out to be only twenty strong and were overwhelmed, but the British lost three more men and gained another nine prisoners. The ‘guide’ was shot on the spot.

By now there was no food at all nor, despite the intermittent rain, any drinking water. The group kept moving all day without food or drink, afraid to rest in case the Bolos caught up with them. During the night the enemy attacked again. The British suffered only one man wounded but many prisoners were hit in the fighting—according to Heathcote forty were killed or wounded, while the Bolos lost eighteen dead. The prisoners had been taking every opportunity to bolt and one of the British now suggested shooting those that remained. The officer with them would not allow it, but only because they were still useful for carrying the stretcher cases.

By the Monday night the group had been without water for twenty-four hours and without food for forty-eight. All day Tuesday and Wednesday they trudged aimlessly in the forest, though they found good water on the Thursday. Frequently they heard Bolshevik patrols passing close by.

At five o’clock on Friday morning they were surrounded and attacked again. The fighting lasted an hour and they lost four killed and several wounded. At seven the Bolos renewed the attack. Heathcote grabbed a rifle from a dead man and did his best. By eight o’clock things must have looked all up for them. The ammunition was almost finished, they were weak from hunger and tired beyond description. In a masterpiece of understatement, Heathcote conceded their position was ‘pretty serious’.

The Bolos charged a third time. The fighting was hand-to-hand when suddenly a cheer went up. After that, Heathcote himself remembered nothing, but a force of fifty to sixty fusiliers had chanced on the scene and saved the group from being wiped out. Heathcote could only recall some rum being forced through his lips, then six hours later waking to find himself being carried through the forest to an aid post. By the next day he was at a casualty clearing station.

According to Heathcote, his party of forty-two had been reduced to sixteen, of whom only three were unwounded. His figures, he says, came from a mate in hospital and are clearly inflated. There is no exaggeration, though, about his own condition. Of his injuries, Heathcote says nothing except at the very end of his account where he mentions that his leg was broken above the knee and that when his boot was cut off, his foot was green with gangrene.

Heathcote’s group had not been alone. For days the forests were teeming with lost men from both sides. To help British stragglers find the lines an observation balloon was put up, aircraft circled overhead shooting coloured flares and buglers sounded the rally every half-hour.

Colonel Davies had an easier time but with similar hair-raising escapes.14 During the fighting he and some of his staff had been trying to reach the Sluda column when they found themselves cut off by the enemy sailors. There was much shouting in Russian and a lieutenant went forward to interpret, but failed to return. This left Davies, a Captain Booth, another captain (the battalion chaplain) and two runners.

Hoping to rejoin the force they had left, the five headed north but were fired on. They went east and were fired on again. They turned west and came across three Russian Whites, then three Bolos whom they took prisoner. It was raining heavily and mortar shells were landing all around them.

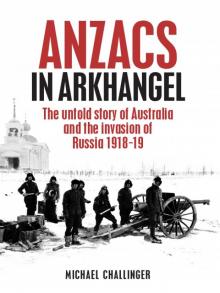

An observation balloon on the Dvina near Troitsa. Usually used for artillery spotting, it was sent aloft after the offensive to help stragglers in the forest find their way back to the British lines. (GAOPDF)

At one point they stopped to rest and the Bolo prisoners, anxious to please, kindled a fire to make them some tea and dry the officers’ socks. The next day the group came across fresh hoof-prints and bloodstained bandages. Thinking them Bolshevik, the Russians, both Red and White, dived for cover. In the confusion, the officers were split up.

Davies’ party was now down to himself, Captain Booth, one Bolo and two Whites. They wandered through the forest looking for the padre’s group and blundered into a swamp. An evening meal of biscuit and sweetened water was cut short by rifle fire. It started raining again.

In the morning they reached a huge marsh and caught sight of th

e observation balloon in the distance. Captain Booth climbed a tree and took bearings and they made their way back to the lines—though a British sentry almost shot them by mistake at the last moment.

On the way, the tame Bolo had carried Davies on his back across a few small rivers, so Davies returned the favour by arranging a staff car to give him a lift to the prisoners’ compound. Davies and Booth had been rumoured captured and intelligence officers had already notified headquarters they had plenty of Red commanders and commissars in the cage available for immediate exchange.

The captured Bolo joined about 2000 other prisoners, while enemy dead were estimated at 500 and wounded at 800. In addition, about 300 Bolos on the east bank had been incapacitated by gas. Total enemy losses were therefore calculated at 3600, more than half the Red Army strength on the Dvina. Much war material had also been captured: 18 field guns, 50 machine guns, 2600 rifles plus mortars, transport, telephone equipment and thousands of rounds of ammunition.15

British losses were much lower than anticipated. Contrary to Heathcote’s figures, they totalled 145, of whom fewer than 30 were killed.16 One of the dead was Lord Settrington. He died in hospital at Bereznik on 24 August from heart wounds. Rawlinson personally cabled the news to the Earl of March. ‘Very sad’, he noted in his diary.17

Bolo prisoners captured in the Dvina Offensive. Most were conscripted men who would have shared the views that General Dunsterville recorded of their counterparts in the Caucasus: ‘I am a Bolshevik though I do not know what Bolshevism is as I cannot read or write; I just accept what the last speaker says. I want to be left alone and helped to go home.’ (GAOPDF)

A month later, the War Office announced that Sullivan had been awarded the VC. Two other Australians were also decorated for their part in the crossing: William Robinson and Joe Purdue both won the DCM. For his part, Sullivan insisted he had done no more than any of his mates, and suggested the medal be raffled. Later, in October, he wrote to his parents from the troopship taking him back to Britain. It is his only letter from overseas still in his family’s hands.

Now we are out of Russia I can tell you that our battalion did a bit of fighting and that I was in most of it. I didn’t tell you before as I didn’t want you to worry. You will be pleased to hear that for pulling a few chaps out of a marshy river under fire on 11th Aug. I have been awarded the VC. I can’t say that I earned it but there were none in the Battalion up to then & I suppose they wanted someone to get one.18

Sullivan was always modest about the award. He later said: ‘It was not much to talk about. I was just lucky because several officers were looking on.’ It doesn’t detract from his courage to wonder whether he would have received the British Empire’s highest decoration if the first man he rescued had not been the grandson of a duke.

Another Australian decorated for his role in the Dvina Offensive was Sergeant Herbert Gascoigne-Roy of Sydney, who earned a DCM. Gascoigne-Roy was serving with the 46th Battalion of the Royal Fusiliers and fought on the east bank of the river, where operations went more smoothly than they did on the west. He led a section in the assault on the village of Gorodok, the major objective on the east bank.

One last award is worth mentioning. The English major who commanded the Gorodok column received a bar to his DSO.19 His name was Arthur Percival and by a tragic irony he was to become better known to Australians in 1942. As the British commander in Singapore, Percival was to sign the most ignominious surrender in British military history and deliver 60,000 men into Japanese captivity, a quarter of them Australians.

13

THE RAILWAY

OFFENSIVE

AUGUST 1919

ON the Railway Front relative quiet prevailed. The late summer rains had finally arrived and heavy rain fell for days at a time. On 15 August the first frost was recorded.

The wet weather did not mean inactivity. Patrols went behind enemy lines almost every day, penetrating as much as 15 kilometres, sometimes almost to Yemtsa. They mapped the enemy’s positions, studied Bolo working arrangements, counted trains and transport, traced telephone wires and took prisoners. Wilfred Yeaman mentions one patrol bringing in a Bolo they had caught 8 versts behind his lines; when they bailed him up he was singing to himself, holding a cooking pot in one hand and a revolver in the other!1

Yeaman was a machine-gunner, one of twenty-five in his section. Their sergeant was Charlie Oliver and their lieutenant (later a captain) an Englishman with the memorable name Curtis Lamond Snodgrass. For a time, the group were based on the forward line at Verst 445, where they themselves were subject to Bolo infiltration. Some nights the sentries heard movement and raised the alarm; occasionally Bolo footprints were found the next morning.

Nor did the men trust their Russian allies; Yeaman’s group in Blockhouse 5 suspected the Russians in number 6 of using their light to send messages in morse. And when the Russians on either side of them practised shooting, it may not have been accidental that they ‘put odd shots precious close to our possie’.2

Days were spent on fatigues—fetching water and rations—and in improving their defences. They installed sandbags, cut logs, extended breastworks, laid coils of wire. But there was recreation too: hours were spent reading, playing cards or just loafing.

On 18 August Yeaman and his mates were moved back to Obozerskaya for a spell. They went to the aerodrome where the Russians had organised a sports meeting. ‘Cossacks do some good trick riding. Village folk turn up rigged out in their Sunday best wearing the gaudiest colours imaginable.’3 On most nights films were shown, though Yeaman doesn’t give their titles. In 1919 films were still silent and the selection may not have been too thrilling. After the Allies withdrew, the Russians inherited the films left behind, including ones such as Why America Declared War, complete with captions in English they couldn’t understand. By that time film shows in Arkhangel were free as the rouble had lost all value and it wasn’t worth anyone’s while to charge admission.4

Two Diggers from No. 2 gun crew of the 201st Machine Gun Company occupy a fortified position taken from the enemy. The wheeled machine gun visible is one of several captured from the Bolsheviks and is now mounted against a possible counter-attack. (AWM A03722)

Yeaman’s diary records other incidents, some mundane, some significant. A pay rise is announced. Churchill is quoted saying that all troops will be out of Russia by 1 November. A British plane crashes when its engine cuts out, but the occupants survive with only minor injuries. It is payday and Yeaman draws 25 roubles.

After a week the group moved back to the support line at Verst 448. They settled themselves into a blockhouse among British and Russian troops. Yeaman mentions the rheumatism in his knee is painful, then adds some important news.

Generals Ironside and Rawlinson visit 448 and the surrounding blockhouses. Rains most of the afternoon. Turn in about 9. At Obozerskaya before leaving, General interviews Harcourt’s force and tells us we are going to attack Bolos and take his guns at 441 in conjunction with Russkies. Do cooking for dinner and tea.5

After the success on the Dvina it was questionable whether an offensive on the Railway Front was needed at all. From the British standpoint, it wasn’t; the enemy had already taken a severe blow and the Bolo threat was much diminished. Furthermore, the British withdrawal was now public knowledge in Arkhangel and it clearly wasn’t in the Bolshevik interest to impede their departure.

It was only at Russian insistence that the offensive went ahead. The man behind it was General Yevgeny Miller who, in spite of his English surname, was a Russian. A professional soldier of thirty years’ experience, Miller had replaced General Marushevsky who had been shifted sideways. In military terms this was a marked improvement, but politically Miller was a diehard monarchist and even more right-wing than Marushevsky. Since Tchaikovsky had been shunted off to Paris as a member of the ‘White Russian Council’, Miller had assumed full power and was running Arkhangel as an out-and-out military dictatorship. The Railway Offensive was formally in

Miller’s hands. Its aim was to clear the Bolsheviks out of Yemtsa.

Yemtsa was about 50 versts south of Obozerskaya. Some histories describe it as a ‘substantial’ town, but it is hard to believe it was ever that. Though strategically important, it was just a village. It had been occupied by the Bolsheviks throughout the winter and was their northernmost base on the railway.

The offensive was the first over which the White Russian Army was to take operational control. The Australians were to spearhead the attack, but they were the only non-Russian ground force involved.6 The British assigned them because they were bold and proficient shock-troops, and perhaps also because they were seen as more expendable than Britons. Otherwise, it was a wholly Russian show. Extra White troops were brought in from the Dvina, together with artillery.

The Whites seem to have been over-exuberant and their preliminary barrage started well before the infantry columns were on the move. At 3 am on 27 August all the guns around Yeaman’s camp, including the armoured train, opened fire and continued at full bore till eight. It was the next afternoon before the Aussies made ready to move off.

A detachment of Cossacks had lent Yeaman’s section fifteen packhorses and the Diggers started to load them with their ammunition and stores. But the horses wouldn’t cooperate. They understood only Russian commands—and a Tartar variety of Russian at that. Some horses refused to budge; others kicked and bucked around the camp, spilling their loads. There were circus scenes as the handlers tried to control them.

Verst 448. The Australian machine-gun section (without their Cossack packhorses) before moving off on 28 August 1919. Railway wagons stand behind them. One of the men displays a faded Australian flag. (AWM A03723)

ANZACs in Arkhangel

ANZACs in Arkhangel